Industry Evolution by Meteor Strike

Two recent developments in the world of comic books have lessons for all businesses in the age of digital transformation.

Before we get to today's main topic, some miscellaneous goodies…

This is the 35th issue of The Dispatch, launched in February of this year. Thank you for joining me on this weekly journey!

Drive-by idea: although the acceleration of polarization happens online, people still find a lot of the raw material for polarization on TV and radio, so why not restore the FCC Fairness Doctrine that went away back in 1987? Would people who hang out on the lower-left and lower-right corners of The Media Bias Chart benefit from hearing opposing views integrated into their new consumption? I think so. Since the Fairness Doctrine always came from the Executive Branch, restoring it might not need to survive the Legislative Death Race.

When does a cover of a famous song become a standard? I’ve been thinking about this for years, and I still don’t know beyond “when people hearing a song don’t think about the original.” Two interesting covers of “Under Pressure” by Queen and David Bowie floated across my awareness this week. The first is Karen O (from the Yeah, Yeah, Yeahs) on lead with Willie Nelson backing her with his unmistakable voice and phrasing. Listen on Spotify here. The second is Bowie himself with Gail Ann Dorsey singing the Freddie Mercury part while also playing the iconic John Deacon bass line. You can find it on Spotify, but you’ll be blown away by Dorsey if you watch it on YouTube. These are still covers. Will the song become a standard in my lifetime?

Bob Lefsetz has a terrific issue about how ads won’t save Netflix.

I am on the horns of a dilemma about Maggie Haberman’s new Trump book, Confidence Man. On one hand, I think highly of Haberman as a reporter and want to read the book. On the other hand, buying the book only adds oxygen to the Trump flame—only increases the Attention Quotient (AQ) of a creature of the media who thrives on that attention and withers away without it—which I’ve argued against before. I’ve split the difference by putting myself in line to borrow the book from my local library: when I last checked there were 133 people in front of me.

I’m now 2/3 of the way through my re-watch of Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, and it has started to go off the rails. Sorkin is at his best when he focuses on the rooms where things happen, whether those rooms are the Oval Office, a newsroom, a sketch comedy show, or a small town in Alabama. Once he leaves the room, things get soapy.

Please follow me on Twitter for between-issue insights and updates.

On to our top story...

Industry Evolution by Meteor Strike

From the “Big Story You Haven’t Noticed” department: this month, two things happened in the world of comic books that combine to make a huge inflection point. My friend Peter Horan calls this sort of thing a “meteor strike” where “the expected only wounds you; the unexpected kills you.”

First, GlobalComix and Ox Eye Media announced a new joint venture: an on-demand comics printing service called GC Press:

GlobalComix has announced it will partner with Source Point Press parent company Ox Eye Media starting in 2023 to form GC Press, an on-demand comics printing service. This will be the first of its kind in the comics industry, allowing readers to purchase any comic in physical form (regardless of retail availability) and have it shipped directly to them, anywhere in the world.

Readers can’t buy Print-On-Demand (POD) issues of big publisher characters like Spider-Man, Batman, or Hellboy comics via GC Press (although I am amused by “The Scintillating Spider-Squirrel,” which seems more homage than parody). Instead, this is a niche service that enables niche writers to monetize their work via POD.

Second, the already ridiculously named DC Universe Infinite digital comics service got an even more ludicrous name for its new top level subscription: DC Universe Infinite Ultra. (What’s next? DC Universe Infinite Super Bat Ultra Plus?) For $99.99 per year, readers get digital access to DC comics one month after they hit comic book shops and the bookstores and newsstands that still carry comics. Prior to this, for $74.99 per year readers got digital access to DC comics from six months ago.

So what’s the problem? Why do these two things make a meteor strike?

It wounds the physical comics market, and it kills the collectibles secondary market.

With DC Universe Infinite Ultra, I can’t imagine buying a physical DC comic again.

I’ve been reading comics since I was five years old, stopping and starting, accumulating thousands of issues in my garage and a very patient wife along the way. Since I first subscribed to DC Universe, my physical comic book purchasing almost stopped, but not entirely. I’d buy non DC comics, and once in a while a DC series (like the various incarnations of Batman: White Knight) would so capture my heart that I couldn’t wait six months to read it.

But I can wait a month for any title. I don’t think I’m the only one.

The new Ultra service will hurt comic book shops, which is where readers go to discover titles that they wouldn’t ordinarily have heard about, and which depend on the most-famous characters from the big publishers (like DC and Marvel) for a lot of their revenue.

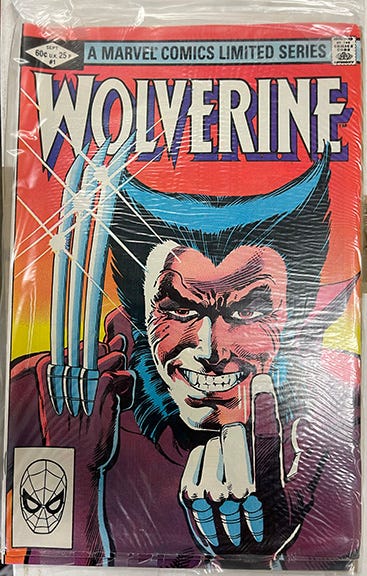

Recently, I found my copy of Wolverine #1 (from 1988) in my garage:

It’s in great shape. If I sell it, then I might make a few thousand dollars. (One copy fetched $17K a while back.) That’s not bad for a 60¢ purchase 35 years ago.

This will never happen for a POD comic. The new GC Press POD service creates nice-to-have physical copies of comics you like, but these copies have no resale value. What counts as a first edition in an on-demand world? If the bigger comics publishers ever start their own POD services, then that will kill the collectibles market for new comics.

The digital transformation of comics books has already been going on for a while. My son loves the words-with-pictures format, but he reads manga and Webtoon. He only rarely buys or borrows physical comics. He is far from alone.

These moves cement my sense that comic books today are only sources of IP for movies, television, and video games, which is sad.

Why all this matters outside the world of comic books.

We have seen this phenomenon before: an old analog form of distribution atrophies in the face of digital transformation, opens up production to new players, but it also kills the businesses of older players that depended on analog distribution to create moats around a value proposition.

Owners of those moats mistake the nature of customer loyalty. They think the customer is loyal to a physical distribution mechanism, but really the customer is loyal to an experience. It’s not CD buyers; it’s music fans. It’s not book buyers; it’s readers. It’s not DVD collectors; it’s movie buffs who stream.

As I’ve written elsewhere, behavior is liquid: you can pour it from one container into another. This is bad news if you’re in the container-selling business and worse if you’re in the container re-selling business.

Newspapers: as my friend and colleague Jeffrey Cole has observed many times, every time an ink-on-pulp newspaper reader dies he or she is not replaced. News organizations don’t have an audience problem; they have a revenue model problem. Americans are more interested in the news than ever before and consume more of it, but they don’t do it on ink-and-pulp. Some old newspapers have transformed to survive (The New York Times, The Washington Post), while new digitally native players arose (blogs, Buzzfeed), but many towns in the U.S. no longer have a local daily paper.

Music: a closer analog to comics is the music business. For the monthly cost of a Spotify subscription (or a willingness to listen to ads) an infinite amount of music is always at our fingertips. I have hundreds of CDs (yep, same garage), but I haven’t listened to one in years. Few people feel bad for the RIAA that waged war on digital music for decades, and more musicians can make a living (although not a Rolling Stones living) today than when the RIAA’s labels ruled, but what about the local record store where people go to learn about new music? Does the movie High Fidelity even make sense to people born after Napster?

There will never be another Beatles, Stones, Olivia Newton-John, Springsteen, Tupac, or Spice Girls because the mass culture moats that accelerated their stardom are gone.

Likewise, although there are more new comic creators working today than ever before, and many of them are supporting themselves as artists, there will never be another Superman, Spider-Man, or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

This isn’t just because the earlier hits came first: it’s because the earlier hits didn’t have to contend with media fragmentation and ephemeral digital culture.

Thanks for reading. See you next Sunday.