When Great Artists Are Bad People

Artists can have dark sides, some alleged and some convicted. Should evil actions by artists change how we experience and judge the art? (Issue #152)

Before we get to today's main topic, some miscellaneous goodies and things worth your attention…

Thank you to everybody who wrote or texted or called or commented last week about my family and friends displaced by the Los Angeles wildfires. My parents and daughter are safely back in their homes, to my immense relief. Other friends and family are still banished from their homes or have lost everything. This is far from over, as a look at Cal Fire's map of the Palisades Fire will instantly show. Climate change is real.

One reader, Perival, mentioned the 1991 Berkeley-Oakland fire. I lived through that one, too... how could I have forgotten? My landlords, Hans and Sigrid, lost their house in the hills and moved into an empty unit in the building. One of my professors also lost his home. It was scary, but I think it affected me less than other crises because it was just me in the middle of it all rather than faraway loved ones.

I enjoyed The Anti-Social Century by Derek Thompson in the latest issue of The Atlantic ($). Thompson explores the differences between solitude and loneliness as well as how technology enables us to spend more time alone.

Other than "quite a coinkydink," I don't know how to describe the juxtaposition of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day tomorrow with the second inauguration of Donald Trump. Dr. King's day is always the third Monday of January (to create a long weekend). Will the president make a thoughtful comparison between the protests that Dr. King led with the events of January 6, 2021? I doubt it, but I'd like to be wrong.

ICYMI, this New York Times Magazine ($) article about how drones have changed the war between Ukraine and Russia is chilling and fascinating.

Ring Cycles: So many magazines arrive at my house that I usually don't dig into the shorter pieces, which is a fault on my part because it means I miss delightful writing like Adam Gopnik's piece about the decay of Saturn's rings in a recent New Yorker ($) that contains sentences like this:

One of the emerging truths of the cosmos is that some of the same laws of slow contingency and evolutionary drift, of vertiginously changing vantage points oscillating with incremental processes, that govern our paltry lives also affect the large stuff out there.

Wow!

On the lighter side, La Profesora and I rewatched the 1995 Pride and Prejudice adaptation (with Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth) on Hulu. It's so good!

Practical Matters:

Sponsor this newsletter! Let other Dispatch readers know what your business does and why they should work with you. (Reach out here or just hit reply.)

Hire me to speak at your event! Get a sample of what I'm like onstage here.

The idea and opinions that I express here in The Dispatch are solely my own: they do not reflect the views of my employer, my consulting clients, or any of the organizations I advise.

Please follow me on Bluesky, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Threads (but not X) for between-issue insights and updates.

On to our top story...

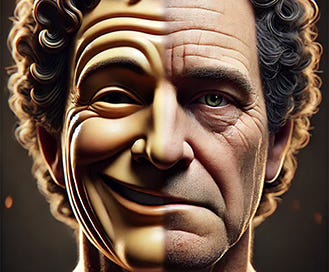

When Great Artists Are Bad People

Let's start with two thought experiments.

#1. How would things be different today if newly uncovered evidence revealed that William Shakespeare was a pedophile who assaulted the boy actors in his company? Would we still teach his works? Would Shakespeare festivals around the world quietly change their names? Would more traditional Shakespeareans start to believe the various "Edward de Vere was the true author of the plays" nonsense conspiracy theories to distance the plays from the predator?

#2. What would happen in the art world if we learned Pablo Picasso was in reality just a bon vivant, and the true creator of the paintings we have mistakenly attributed to Picasso was Adolph Hitler? Today, the only person who seems interested in Hitler as a painter is Harlan Crow, the Texas billionaire who collects the paintings and takes Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas and his wife on luxurious vacations that Justice Thomas then doesn't like to disclose. But if Hitler turned out secretly to have been one of history's best painters, how would that change our views of the paintings? Would it also change our views of Hitler? (I hope not.)

I pose these thought experiments because two recent articles surface similar questions about what it means when great artists, in these cases great writers, turn out to be bad people.

The question at hand is what should fans of those artists do with this news?

In the January 13 New York Magazine ($) cover story, There Is No Safe Word, Lila Shapiro explore allegations that beloved fantasy writer Neil Gaiman has sexually assaulted a lot of young women. Master, a British podcast (and also what Gaiman allegedly likes women to call him), first broke the story about Gaiman last summer. He denies everything. Shapiro has extended the coverage, including a thoughtful and painful re-reading of "Calliope" (Sandman #17), where the writer/villain, Richard Madoc, rapes the Greek Muse Calliope to cure his writer's block. Madoc turns out to be the analog for Gaiman rather than the Sandman hero.

In the December 30/January 6 issue of The New Yorker ($), Rachel Aviv's article You Won't Get Free of It explores how Nobel Prize winner for Literature Alice Munro allowed her second husband to sexually abuse her daughter from her first marriage. To extend that horror, Munro used the abuse as material for her short stories. "Her writing was more real than our lives and, I think, our existence," one of Munro's other daughters said. As with the Gaiman article, this is not a new story, but Aviv digs more deeply.

I've never read an Alice Munro story, but I've read a ton of Neil Gaiman's work. In grad school, my friend Cyn, another Gaiman fan, and I went to see him speak. The Sandman comic book series is a favorite: I have every individual issue and the trade paperback collections. If I believe the allegations, then should I stop reading Gaiman? Wait to see if he gets charged and convicted? Hold onto what I have but refuse to spend money on his future writing? Not watch TV shows and movies based on his works? Those last two actions wouldn't just be protests against Gaiman: they'd also hurt the editors, publishers, producers, and performers who create the books and adaptations.

At what point and how should an artist's behavior affect how we experience and judge the art?

I adored the comedy of Bill Cosby as a kid; entire routines are inscribed on my memory. Cosby was convicted of sexual assault and imprisoned, freed because of a violation of due process, and still faces multiple civil suits. Few serious people doubt that Cosby is a predator. Should that change the pleasure we take in watching reruns of The Cosby Show or listening to his old comedy routines? If so, how?

How great does an artist have to be before that greatness excuses terrible behavior?

In his recent Netflix standup show Selective Outrage, Chris Rock observed:

One person does something, they get cancelled. Somebody else does the exact same thing… You know, like the kind of people that play Michael Jackson songs, but won’t play R. Kelly. Same crime. One of them just got better songs.

Jackson was accused and Kelly was convicted of sexually abusing minors. I thought about this last week when I was in Las Vegas for CES. My hotel was near the theater where Michael Jackson ONE by Cirque de Soleil was playing. A more traditional tribute show, MJ Live, is playing elsewhere. To my knowledge, neither show acknowledges the accusations against Jackson. The tributes are unironic.

There is no tribute show for R. Kelly: will there be after Kelly dies? (He's only 58, so we won't know for a while.)

The bad actor has to be close to the creation of the art for moral qualms to come up. Harvey Weinstein is an imprisoned predator, but I've never heard anybody feel trepidation about re-watching Pulp Fiction or Shakespeare in Love. Weinstein produced rather than directed those movies. On the other hand, lots of people won't watch Woody Allen movies anymore because of the allegations that the director abused his adopted daughter, Dylan Farrow. (His marrying Soon-Yi Previn, the adopted daughter of former partner Mia Farrow, also creeps out some folks.)

For recovering English Majors like me, some of these questions give present-day urgency to old lit crit ideas. In "The Death of the Author" (1967), Roland Barthes argued that readers should ignore everything about an author's biography and intentions, which have no bearing on the meaning of a text. Two years later, Michel Foucault counter argued (in "What Is an Author?") that an "author function" determines how art works in society and how authorship defines a set of different works: e.g., Mark Twain's novels, stories, and letters count as part of his oeuvre, but his grocery lists do not.

It sure would be convenient for fans of Gaiman, Allen, Cosby, Jackson, Kelly, and Munro, if we lived in a world according to Barthes, but we don't.

Will I ever listen to "The Dentist" by Cosby, read Gaiman's Sandman, or listen to "Thriller" with the unalloyed pleasure of the past and without a twinge of guilt and doubt? Only time will tell.

Thanks for reading. See you next Sunday.

* Image Prompt: A comedy tragedy mask—with a smiling happy face on the left half and a frowning sad face on the right half—with a photorealistic human face... a 60 year old white man with curly dark hair.

Thank you, Retsu, for reading and for sharing. I will *definitely* read this piece!

Picasso was a real asshole to the women in his life, too, as I understand it. And no, I don’t think a reasonable, considerate person should be able to enjoy the art of a truly awful person without that reality in our minds. Why should we?