Why People Believe Conspiracy Theories

What makes people believe nonsense for which there is no evidence?

Before we get to today's main topic, some miscellaneous goodies…

No newsletter next week!

Virtual Models are real: just one week after I wrote about virtual models in the old movie Looker, my friend Tom Cunniff posted about how a company called DMix has made them a reality. #creepy

Speaking of last week’s piece, the Eagle Eye Award goes to Andy Maskin, who noticed that autocorrect had changed “Daddy Warbucks” to “Daddy Warlocks,” which is funny but ouch! You should read Andy’s recent piece about ChatGPT.

This New Yorker piece, “Are You There, Margaret? It’s Me, God,” made me laugh.

Thanks to Mike Shields for including a quote of mine in his recent issue about why President Biden needs to appoint an ad tech czar.

Please follow me on Post and/or on LinkedIn for between-issue insights and updates.

On to our top story...

Why People Believe Conspiracy Theories

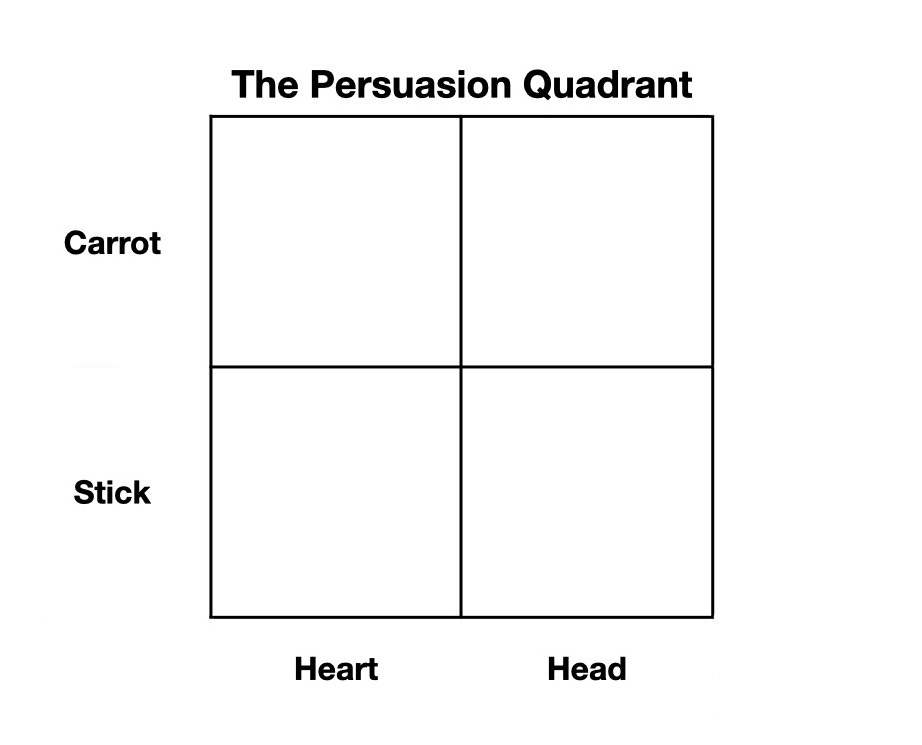

As I first wrote a year ago, you can see the elements of persuasion in this simple quadrant:

Mostly, people decide with their hearts and then justify with their heads. They’re also more keen to avoid loss than to pursue gain. Knowing where your argument sits on the quadrant can help you to be more persuasive.

This time, I want to flip to the other side and dig into why people abandon their heads altogether to believe nonsense.

I got to this topic by way of an email my friend Robert Moskowitz sent a few days ago about conspiracy theories:

It occurs to me that people who subscribe to conspiracy theories are only partially affirming that their theory is correct. An equal or perhaps larger part of the basis for their belief may be their desire to deny the reality that they don't like.

Hence, it's sensible to believe that reptile alien shapeshifters are running our planet because it's uncomfortable to acknowledge that legitimately elected human leaders are making the decisions that seem so wrong-headed to the conspiracy theory believer.

This idea was so interesting that I asked Robert if he minded me digging into it here, and he kindly said go right ahead.

I like the neutrality of Robert’s articulation. It’s a projection test: you can lean politically in either direction and still see the other side in that account. It’s also generous and empathetic to the conspiracy theorists out there.

I’m less generous and less empathetic to these folks. Although I think Robert is accurate, I also think his account is incomplete.

On top of believing an unbelievable theory because reality itself is unpalatable, conspiracy theorists engage in two bad habits of thought.

First, conspiracy theorists choose tribal affiliation at the expense of evidence.

Belonging can be more important to people than truth. When a person’s beliefs conflict with the data or lack of data—what psychologists call cognitive dissonance—then that person is more likely to dismiss the data than to change the beliefs. “Sure, cigarettes cause cancer, but that’s for other people. I have strong genes because my Uncle Bernie smoked two packs a day and lived to 90.”

With conspiracy theories, people usually don’t think that their own group has been taken over by the Skrulls (the shapeshifting reptile aliens from Marvel comics and movies). It's the other people.

It's hard to make generalizations about groups that you know. When you know a group and can differentiate among members of that group, then you don’t clump them together into an “other” category that you fear, persecute, or regard as inferior.

One hint that somebody is participating in a generalized othering of another group is when you hear that person say something like, “some of my best friends are….”

A technical term that psychologists use for this kind of other is “out-group.” The “Out-Group Homogeneity Effect” explains how we generalize about others:

People judge members of out-groups as more similar to one another than they do members of in-groups. Males may perceive females as more similar to one another than they perceive males and vice versa. Pro-lifers may judge pro-choicers to be more similar to one another than they judge pro-lifers to be and vice versa. Academicians may perceive business people to be more similar to one another than they perceive fellow academicians and vice versa.

The great 20th Century theorist Raymond Williams talked about it this way:

The masses are always the others, whom we don’t know, and can’t know. Yet now, in our kind of society, we see these others regularly, in their myriad variations; stand, physically, beside them. They are here, and we are here with them. And that we are with them is of course the whole point. To other people, we also are masses. Masses are other people. (299)

Othering the masses is a cheap way of consolidating your group identity.

You don’t need a them to have an us, but having a them—masses, others, out-groups—makes creating an us easier, as does accusing them, the others, of enemy action.

This othering, creating a them, is how partisan news stays in business (on either the lower left or lower right side of the Media Bias Chart).

Second, with repetition, conspiracy theories slide from sloppiness into salience.

Faced with insufficient evidence, the first reflex of the conspiracy theorist is to change the subject. This is the whataboutism and false equivalence that characterizes partisan news.

The next reflex is to engage in sloppy thinking: "Well, we don't know that alien lizards aren't running the government.”

But it’s impossible to prove a negative. That’s why courts don’t proclaim that somebody is innocent when there isn’t sufficient evidence to convict: instead the accused is “not guilty.”

Over time, and with lots of repetition, the conspiracy theorist’s double negative of "we don't know it isn't" slides into a simple positive: alien lizards are running the government.

Repetition builds salience. The more you repeat a statement, the more thinkable it becomes even if you know that there’s no proof for that statement. This works with harmless marketing slogans (do we have evidence that people are loving McDonald’s?) as well as with sinister propaganda.

Hitler knew about salience, which is why he repeated his lies about Jews over and over. More recently, the former president’s habit of bestowing memorable nicknames on his opponents (Crooked Hillary, Little Marco, Sleepy Joe, Low-Energy Jeb) and then repeating them over and over made those nicknames inescapably thinkable.

I don’t know if there’s any way to detach a person from a conspiracy theory, but I do know that presenting evidence by itself doesn’t work. To change somebody’s mind about an out-group, you need to move that out-group closer, as close to inside as possible.

If there is no them, then there is only us.

Thanks for reading. See you in two weeks!

Thanks for reading, Rich! I appreciate the thoughtful comment.

I want to share some responses. They concern a different aspect of the tribal affiliation discussion. The aspect of reality that is unpalatable is group retribution.

Look at the reward:cost ratio of taking a view different from the rest of your tribe (or in-group). Particularly in small communities, the cost of expressing viewpoints not acceptable to the rest can come with a heavy price, including being ostracized. We know a couple who moved here from a town they had lived in for decades when they refused to accept certain tenants of the church that they volunteered in for decades.

Accepting and even promulgating certain conspiracies may well be the cost of belonging. Consider the cost of the alternative. How many stories and myths do we have of the brave individual who went against the crowd? The fact that we consider that brave tells shows how it must typically have some cost.

It may well be that believing that the out-group has pedophilic cannibals (however outlandish) is less costly than breaking with your tribe.