Social Media and the Banality of Evil

Max Fisher’s new book “The Chaos Machine” shows the downside of what happens when companies pursue growth at all costs.

In her 1963 book about the trial of Adolph Eichmann, one of the chief architects of the Nazi murder of six million Jews during the Second World War, Hannah Arendt coined the phrase “the banality of evil” to describe Eichmann’s failure to see the consequences of his actions because he was just doing his job.

I’m always hesitant to compare any group to the Nazis except for the Neo-Nazis who embrace the label. However, as I finished reading Max Fisher’s excellent new book, The Chaos Machine: The Inside Story of How Social Media Rewired Our Minds and Our World, Arendt’s phrase about the banality of evil kept coming to mind.

To be clear, I am not comparing Facebook, Instagram, Snap, TikTok, Twitter and YouTube to the Third Reich. But I am comparing the indifference of those companies to how their pursuit of profits has destroyed lives to the indifference of Eichmann in Jerusalem.

Fisher is a talented reporter for The New York Times. For years, he has been on the ground chasing the stories that make up the book’s main argument: social media companies use sophisticated software (algorithms) that deliberately provoke extreme emotional reactions in users. The algorithms do this by putting agitating content in front of users even though that content is often misinformation or disinformation. More agitated users spend more time on social media and spread the lies, which means that the social media companies can sell more ads and make more money.

Facts move slower than lies, so corrections or comments or warnings to think first and share later don’t do any good.

What are the consequences that the social media companies ignore? The Chaos Machine presents a searing account of how Facebook and YouTube pursued growth at all costs, even though those costs include genocide in Myanmar, a totalitarian regime and accelerated Zika epidemic in Brazil, and the polarization in this country that has divided us more than at any point since the Civil War.

Is Social Media like Cigarettes?

The design ethicist Tristan Harris says of social media that “every time you open an app there are 1,000 engineers behind it trying to keep you using it.”

Throughout The Chaos Machine, both Fisher and different people he interviews compare addictive social media to cigarettes and the companies to Big Tobacco, but I think that’s the wrong metaphor.

It’s difficult but possible to quit smoking on your own. It’s even possible to use tobacco with enough moderation that it is unlikely to kill you… like the person who smokes the occasional cigar. Even though Big Tobacco deliberately reengineered its product to be more addictive, tobacco has been a part of human life for centuries. It didn’t sweep the world suddenly starting in the early 2000s,

The right metaphor is OxyContin. The drug oxycodone has been around for more than a century, but in 1996 Purdue Pharma (owned by the Sackler family) synthesized and started marketing OxyContin. The drug is effective at managing pain, but it is also dangerously addictive. Doctors regularly prescribe too much of it to patients facing either chronic or post-operative pain, which results in rampant abuse and addiction. This helped to create the Opioid Epidemic, and in March the Sacklers settled with a host of State Attorneys General for six billion dollars.

From 1996 to now is a rapid transformation, almost as rapid as the digital transformation that started with Google’s founding in 1998.

As a culture, we’ve realized that we can’t expect opioid addicts to break their addiction through sheer willpower. Breaking a cycle of addiction takes external intervention—addicts need help—which that $6B settlement is helping to fund.

So how can we expect users of social media simply to stop using?

A Distraction to Avoid: This is Not About Freedom of Speech

Fisher is a journalist, so he doesn’t present solutions to the problems he identifies.

This is why he doesn’t do more than glance at Section 230, which is part of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 that absolved internet companies of liability around things that users put on websites.

Conservatives complain about Section 230 because they believe that social media platforms privilege liberal points of view and throttles their conservative counterparts. In reality, and as Fisher documents, conservative candidates and causes have benefited from social media more than liberals.

Section 230 happened in 1996, a handful of years after the invention of the web, but eight years before Facebook (2004), nine years before YouTube (2005) and 11 years before the mobile/social revolution that started with the iPhone (2007). The world of communications that it was reacting to has changed.

Section 230 is overdue for a reset.

Talking about Section 230, people usually focus on what Jeff Kosseff has described as “the 26 words that created the internet,” which is this section:

No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.

But there’s another section immediately after those 26 words that are just as important:

No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be held liable on account of any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected.

The FCC built moderation into Section 230: it expected digital companies to manage what went on their platforms.

As Fisher describes in detail, the social media companies—particularly Facebook and YouTube—have declined to do anything about dangerous misinformation and disinformation.

It’s time for the Federal Government either to insist that they do more or to remove the protections from liability.

This is not a First Amendment issue. That amendment only says that Congress “shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech or of the press.” It doesn’t apply to companies like Alphabet (Google) and Meta (Facebook). Even so, Section 230 says that platforms will not be punished if they restrict access to constitutionally protected content.

This isn’t censorship: it’s simply declining to amplify the reach of a piece of objectionable content, which should include misinformation and disinformation.

As filmmaker Sasha Baron Cohen has observed, freedom of speech is not freedom of reach.

Miscellaneous goodies…

The Washington Post has this article about why mosquitoes find some people more delicious than others.

My friends at the Quarantined Comics podcast kindly invited me to contribute an audio version of last week’s main article.

Thanks to my friend Fawn Fitter for including me in this SAP piece about the future of collaboration.

Who knew that Sesame Street’s iconic Cookie Monster’s real name is Sid?

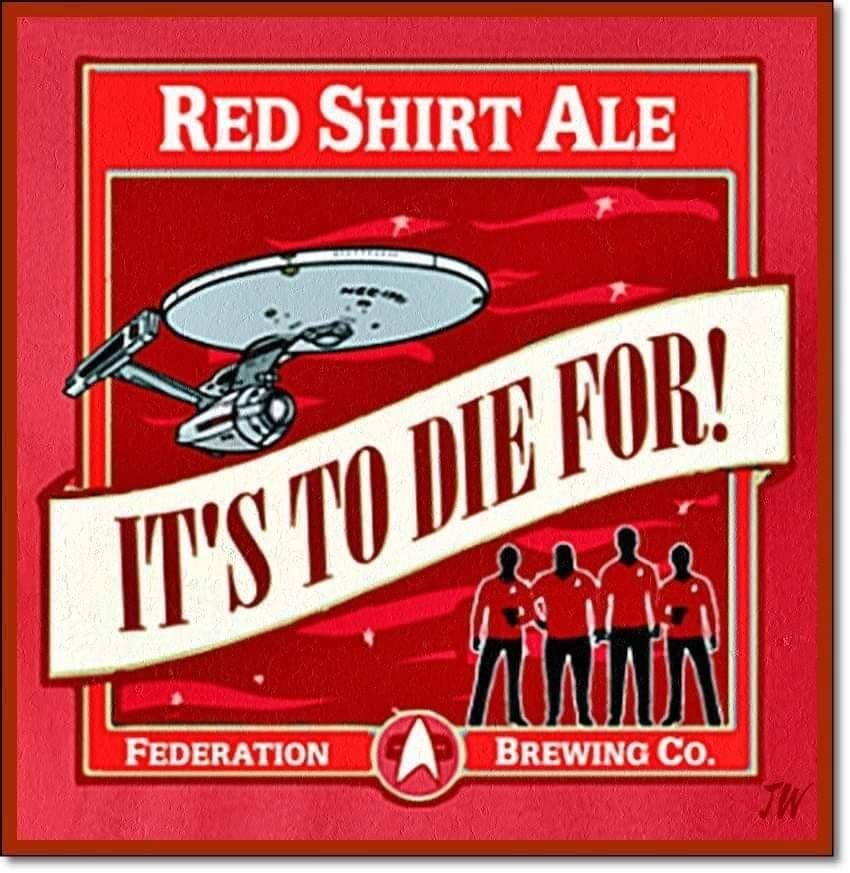

Finally, I can’t tell if there really is a place called “Casa Grunny’s Cocktail Bar” out in the world, but their Facebook page consistently has funny stuff. Here’s one example:

Please follow me on Twitter for between-issue insights and updates

Thanks for reading. See you next Sunday.

Check out “An Ugly Truth,” by Cecilia Kang and Sheera Frenkel. They’re also reporters for The NY Times. The focus is just Facebook, but the conclusion is that Zuckerberg and Sandberg, while not trying to commit evil, were highly involved executives in Facebook’s pursuit of growth at all costs. The banality of the evil is that they just didn’t care that an engagement through enragement business model could tear society apart and then set it on fire.